The Orchestration Bottleneck

Multi-agent AI systems fail when one agent becomes the traffic cop. The orchestrator pattern creates a single point of failure that defeats the purpose of distributed intelligence.

The promise of multi-agent AI is compelling: specialist agents collaborating on complex work, each contributing domain expertise, collectively achieving what no single agent could. A creative agent handles visual concepts. A governance agent maintains quality standards. A research agent synthesizes information. Together, they operate like a well-coordinated team.

The reality is usually messier. Most multi-agent implementations collapse into a pattern that defeats their own purpose: the orchestrator bottleneck.

The Orchestrator Pattern

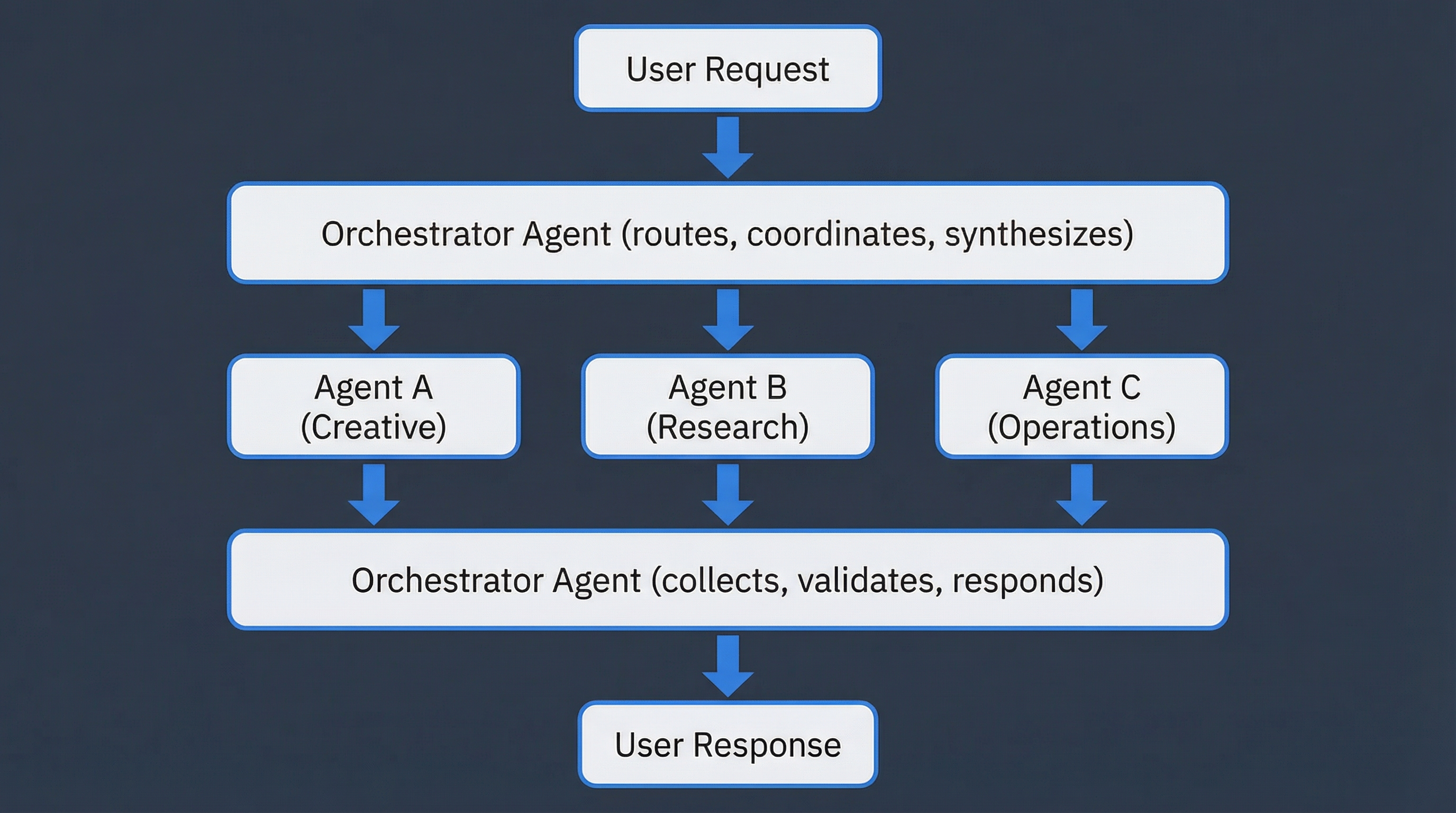

The intuitive approach to multi-agent coordination looks like this:

One agent sits at the center, receiving all requests, deciding which specialist to invoke, collecting their outputs, and synthesizing the final response. This feels natural—it mirrors how human teams often work, with a project manager routing tasks to specialists.

The problem emerges at scale. The orchestrator becomes the bottleneck it was meant to eliminate.

Why Orchestrators Fail

Single Point of Failure

Every request flows through one agent. If that agent misunderstands the task, routes to the wrong specialist, or fails to synthesize outputs correctly, the entire system fails. There’s no redundancy, no peer correction, no collective intelligence—just a traffic cop with too much responsibility.

Context Collapse

The orchestrator must understand every domain well enough to route correctly. Creative requests go to the creative agent. Technical requests go to the technical agent. But what about requests that span domains? The orchestrator makes a routing decision based on its (often superficial) understanding, potentially sending work to the wrong specialist entirely.

Information Loss

When Agent A completes work and returns it to the orchestrator, context is lost. The orchestrator receives a summary or output, not the full reasoning chain. When Agent B needs to build on Agent A’s work, the orchestrator must re-explain—introducing translation errors and losing nuance.

Scaling Ceiling

Add more specialist agents, and the orchestrator’s job gets harder. It must understand more domains, manage more handoffs, and synthesize more diverse outputs. The complexity grows faster than the capability.

Authority Confusion

Who decides quality standards? The orchestrator? Each specialist? When the creative agent and the governance agent disagree, who arbitrates? The orchestrator becomes a judge in domains where it lacks expertise.

The Symptoms You’ll Recognize

Routing failures. Work goes to the wrong agent because the orchestrator misclassified the request. The creative agent receives a technical question. The research agent gets a task requiring judgment calls.

Context repetition. You find yourself re-explaining context that should have transferred between agents. “As we discussed earlier” means nothing when each agent only sees orchestrator-filtered summaries.

Bottleneck delays. Simple requests take longer than they should because everything queues through the orchestrator. Two agents that could work in parallel instead wait for sequential routing.

Quality drift. Standards vary across agents because no shared context enforces consistency. The creative agent uses one tone, the operations agent another. Brand voice fragments.

Debugging nightmares. When something goes wrong, tracing the failure requires understanding the orchestrator’s routing logic, each agent’s internal processing, and the synthesis step. The chain of reasoning is opaque.

The Underlying Assumption

The orchestrator pattern assumes that coordination requires a coordinator—that distributed agents need centralized control. This assumption comes from human organizational patterns where communication bandwidth is limited and shared context is expensive to maintain.

But AI agents don’t have these constraints. They can read the same context simultaneously. They can observe each other’s outputs in real-time. They don’t need a manager to route information—they can share a channel.

The orchestrator pattern solves a problem that doesn’t exist for AI agents while creating problems that do.

What Would Actually Work

The alternative isn’t chaos. It’s recognizing that coordination can be emergent rather than imposed.

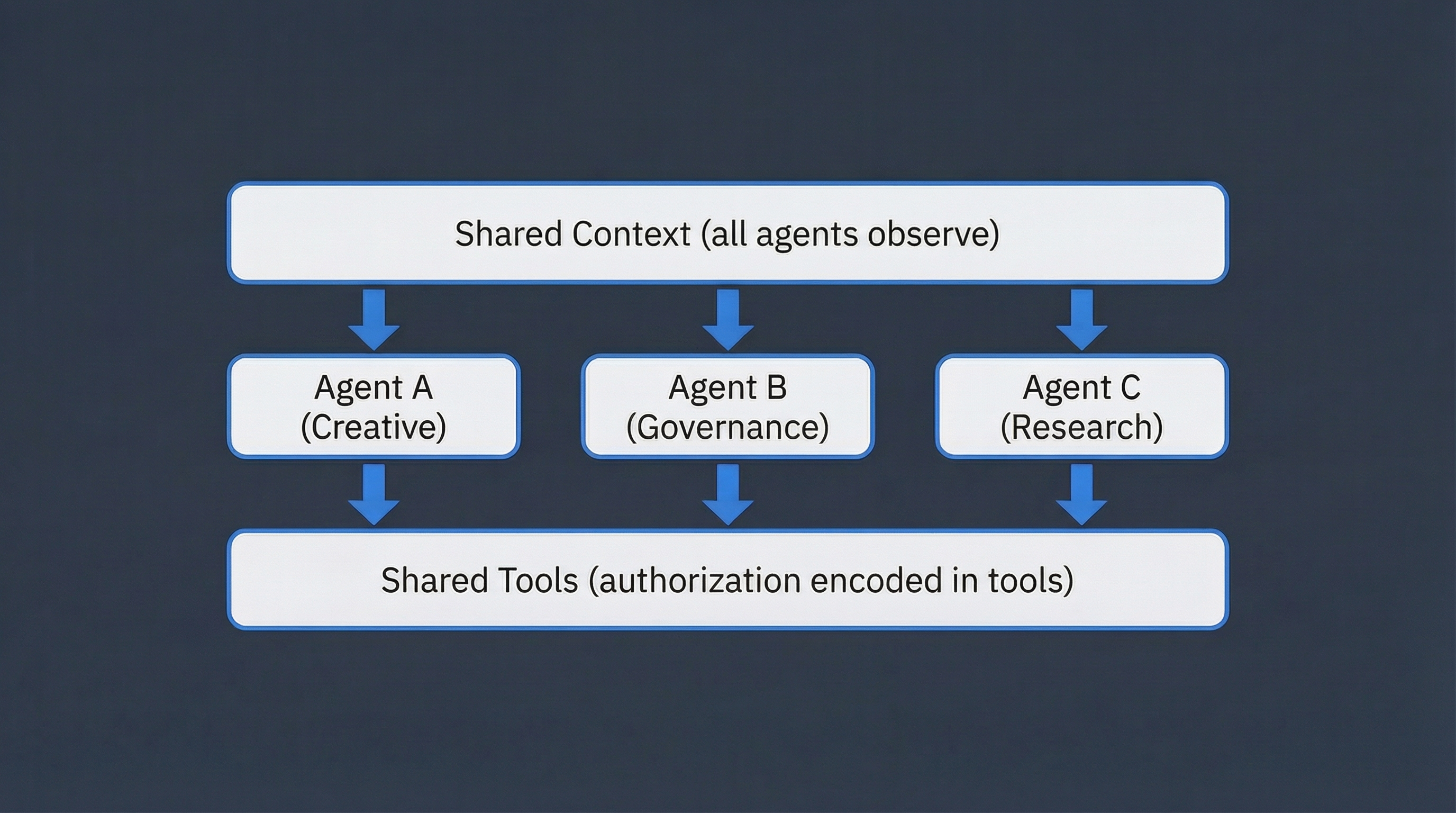

Consider a different architecture:

All agents read the same conversation. All agents can contribute. Tools themselves encode what each agent is authorized to do. No traffic cop—just peers with different capabilities operating in shared space.

This is how effective human teams actually work: not through a manager routing every message, but through shared context and clear role boundaries. The manager steps in for escalation, not for every transaction.

The Governance Question

If there’s no orchestrator, how do you maintain control? How do you prevent agents from contradicting each other, overstepping boundaries, or making unauthorized decisions?

The answer: move governance from the routing layer to the tool layer.

Instead of an orchestrator deciding “Agent A can do this, Agent B cannot,” the tools themselves encode authorization. The task management tool accepts updates from the governance agent but requires human approval for deletions. The content publishing tool accepts drafts from the creative agent but flags anything outside brand guidelines.

Authorization becomes infrastructure, not routing logic. Any agent can attempt any action; the tools determine what succeeds.

This shifts the architecture from “one agent controls access” to “the system encodes rules.” The former creates a bottleneck. The latter creates a protocol.

The Human Role

In orchestrator architectures, the human often becomes another node—receiving orchestrator summaries, approving orchestrator recommendations. The human’s visibility into actual agent work is filtered through the same bottleneck as everything else.

In peer architectures, the human is a participant in the shared context. They see what agents see. They can intervene at any point, not just at orchestrator-defined checkpoints. Transparency is structural, not a feature the orchestrator must implement.

This changes the human role from “manager of the manager” to “participant with authority.” The human doesn’t control the orchestrator who controls the agents. The human operates alongside agents in shared space, with certain decisions reserved for human authority.

When Orchestrators Make Sense

The orchestrator pattern isn’t always wrong. It works when:

Agents truly can’t share context. If agents run on different platforms with no shared state, an orchestrator bridges them. This is a technical constraint, not a design choice.

The task is genuinely sequential. Some workflows require strict ordering: research, then analysis, then synthesis. An orchestrator can enforce sequence. But even here, the sequence could be encoded in tools rather than routing.

Human bandwidth is the constraint. If the human can only review one agent’s output at a time, an orchestrator can serialize and summarize. This is a human limitation, not an agent one.

You’re prototyping. Early experiments often start with orchestrators because they’re simpler to reason about. The bottleneck appears later, at scale.

For mature multi-agent systems doing complex creative or operational work, the orchestrator pattern is usually a phase to grow out of, not a destination.

The Design Challenge

Moving from orchestrator to peer architecture requires rethinking several assumptions:

Context sharing. How do all agents observe the same conversation? What’s the shared state they read from?

Tool authorization. How do tools encode what each agent can do? What happens when an agent attempts an unauthorized action?

Conflict resolution. When agents disagree, how is it resolved? Who has authority over what?

Human integration. How does the human participate without becoming another bottleneck? What decisions remain reserved for human authority?

Auditability. How do you trace what happened when something goes wrong? How do you understand the collective decision chain?

These aren’t trivial questions. But they’re better questions than “how do we make the orchestrator smarter?”—which has a ceiling that peer architectures don’t.

Next Steps

The Peer Agent Collaboration Framework addresses these design challenges with concrete patterns: shared channel architecture, tool-encoded authorization, domain-based self-selection, and human escalation protocols. It’s tested in production at NullProof Studio, where multiple AI agents collaborate on creative and operational work without a central orchestrator.

The goal isn’t to eliminate coordination. It’s to make coordination emergent rather than bottlenecked—distributed rather than centralized. When agents can see the same context, contribute to the same workspace, and operate within tool-encoded boundaries, the orchestrator becomes unnecessary overhead.

Your multi-agent system doesn’t need a traffic cop. It needs a shared road.